By: Steve McClure | Follow me on Twitter @stmcclure1993

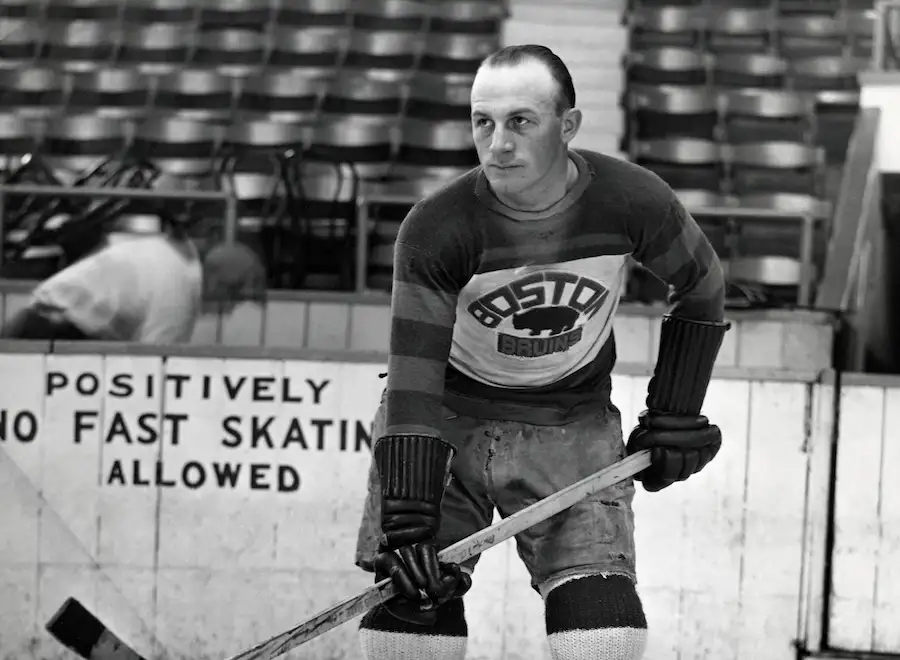

The Boston Bruins’ 1928-29 Stanley Cup-winning year was only Eddie Shore’s third season in the NHL. Yet the ‘All-World’ defenseman was already the league’s greatest defender and the league’s biggest box office draw.

Born in Fort Qu’Appelle, Saskatchewan, Shore clambered up the professional ranks in Saskatchewan before making his mark with the Western Hockey League’s Edmonton Eskimos. Shore played a dazzling brand of hockey; ruggedly physical and fiery, with some locomotive speed, it was in Alberta that Shore became affectionately known as the ‘Edmonton Express.’ Hearing of this dynamic player from the WHL, Boston Bruins owner Charley Adams purchased the rights to Shore and six other players for the bargain price of $50,000 in 1926.

It did not take long for the cantankerous defenseman to stamp his brand of hockey on the organization—a brand that Bruins’ fans have come to appreciate and expect as the team’s core identity for the decades to follow. By all accounts, Shore sought agitation on the ice at every turn—and often found it. His first two seasons in the NHL were rooted in unrest, as he showed signs of provoking the opposition to no end. He led the league in penalty minutes with 136 in his rookie year of 1927 and again with 165 the following year.

In 1929, he was one of the highest-paid professional athletes; including bonuses, he was thought to be commanding a whopping $25,000 salary. This was no doubt a sizable expense for Charley Adams but one well worth the price, as NHL attendance skyrocketed 22% over the previous season’s numbers, and none of the 10 NHL franchises benefitted more than the Boston Bruins. After all, the team possessed a league phenom, and it hungrily welcomed a burgeoning fan base into its brand-new sports arena sitting atop North Station—Boston Garden.

Spectators loved his combativeness and high-flying rink rushes, which often brought people out of their seats. Shore’s 12 goals placed him third on the Bruins in ’29, and his defensive stalking of puck carriers—causing instant fear and agitation—was helping to cement his legendary status. More importantly, his steady play contributed to Boston’s first Stanley Cup title that year, and a decade later, in 1939, he led the Bruins to another taste from the Cup.

Perhaps due to a higher focus on defense, Shore’s career offensive output in the playoffs tended to fall below his regular season productivity; he accumulated only 18 points, seven of which were goals. His most impactful goal was the overtime winner in Game 3 of the 1933 semi-final matchup with Toronto, a series in which the Maple Leafs would later win in 5 games. His willingness to play physically—and on the fringes of legality—did not decrease when it came to playoff time. In 52 career playoff games, Shore amassed 183 minutes in penalties, good for #7 on the Bruins all-time list, but only topped by Derek Sanderson on a per-game basis.

The fiercest incidents appeared to take place against the Montreal Maroons. Perhaps not accustomed to being on the receiving end of such harsh physicality, such as Shore would routinely dish out shift after shift, according to accounts in one game, the entire Montreal team decided to take liberties on the defenseman whenever possible. “It was a whole clan against one man,” Le Canada, the French language newspaper, reported, “and that’s what made the whole affair revolting. It was obvious that it was no longer hockey but a program to get rid of Shore.” Over the course of the game, Shore had suffered several facial lacerations from body checks and handy stick work; in the closing minutes of the game, Shore sustained a hit to the head, leaving him unconscious for a full fourteen minutes. All told, he incurred a concussion, a broken nose, two black eyes, and three broken teeth.

Teams learned very early on that Shore was a force to be reckoned with. Similarly to how contemporary fans will recall opponents’ playoff strategy of targeting Raymond Bourque to wear him down, Shore faced an onslaught of physical abuse routinely. “He was bruised, head to toe, after every game,” recalled Hall of Famer Milt Schmidt, a four-year teammate. “Everybody was after him. They figured if they could stop Eddie Shore, they could stop the Bruins.”

Not known to divulge much of anything to the press, he was a private man who would return back to his 320-acre farm in Duagh, Alberta, just north of Edmonton, at the end of each hockey season. He had bought the sprawling farm for a reported $16,400 in 1928. According to Shore biographer Michael Hiam, the farm housed hogs, cattle, turkeys, ducks, chickens, workhorses, and a bull. Shore paid a hired hand to take care of the farm during the hockey season. There were brief occasions that the Duagh farm would serve as sanctuary away from the Bruins’ winter address, much to the chagrin of Art Ross; brief holdouts in the fall of 1933 and again in the fall of 1938—both following Hart Trophy-winning seasons—proved Shore to be a shrewd negotiator who knew his professional value, and there was also a bout with sciatica, which forced him to miss half the 1936-37 campaign, including the playoffs.

Shore’s playing career was, indeed, punctuated by violent play; most notably, he was involved in a brutal retaliatory hit from behind on Toronto’s Ace Bailey, resulting in a sixteen-game suspension and the unfortunate termination of Bailey’s playing career. He is also revered for epic tales of absorbed injuries and pain tolerance; he supposedly endured over 900 bodily stitches, broken jaws, multiple bone fractures, and a lacerated ear of which—according to a well-worn narrative—Shore demanded a doctor stitch back on without anesthetic (a procedure Shore scrutinized, himself, by the hand-held mirror).

When hockey fans conjure up the image of ‘old-time hockey,’ Eddie Shore is the gold standard, carved out of the stuff of legend—a ferocious dynamo recklessly laying siege to opponents and bringing fans to their feet in dizzying delight. Few of us saw him play. How much of the legend is true? How much is a myth? The following is from a passage in a 1967 Sports Illustrated piece by hockey scribe Stan Fischler: “I see no point in bragging,” Shore says. “I’ve always felt the truth will out.” But, with Eddie, it has been almost impossible to separate truth from fiction. His life and his legend have become too interwoven. His bizarre behavior has been embellished in the stories about him, no doubt, but the stories have roots in truth.” Most of us are a little crazy one way or another,” Eddie Shore says. “Some of us admit it. As for me, I’m not sorry about anything I’ve done in my life.”

Shore was a horse of a player who could, reputedly, be counted on to play fifty-plus minutes per night—authoritatively—when needed. It would be an impossible task to separate the brutality of his playing style from the elite skills that he obviously possessed as if they were equal parts to the player’s whole; the success he reaped was largely a result of the unique nature of his game—a game other players could neither endure nor excel at to the extent Shore was willing to.

That’s the lasting legacy his retired #2 banner has branded on the Bruins franchise. Fierce play and heavy minutes aside, it is the defenseman’s league-wide dominance that will forever be etched in NHL annals; the truest testimonial to his elite accomplishments is that Eddie Shore was a perennial Hart Trophy candidate as the league’s most valuable player, winning the award in ’33, ’35, ’36, and ’38. Two Stanley Cup championships don’t hurt either.

Note: Eddie Shore was a 7X First Team All-Star and a 4X Hart Trophy winner as league MVP—only bested by Gordie Howe and Wayne Gretzky. He was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1947 and named to the Boston Bruins’ All-Centennial Team in 2023.

(Credit to puckstruck.com blog for the Shore/Maroons incident, Stan Fischler’s Sports Illustrated quotation, and Krystle Dodge’s Hockey Inflation piece for Shore’s 1929 salary)

Leave a Reply