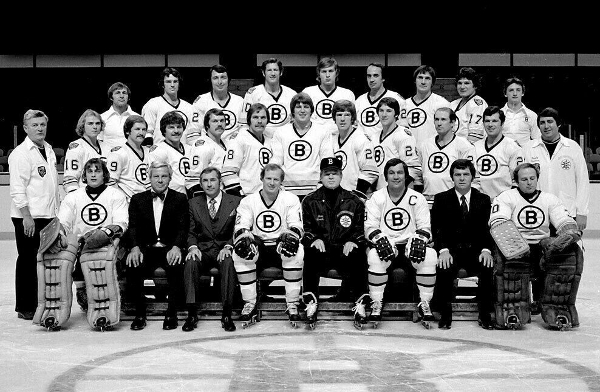

By: Steve McClure | Follow me on Twitter / X @stmcclure1993

In the summer of 1976, while the city of Boston was celebrating the country’s bicentennial, the Bruins were looking to bolster their NHL lineup. They thought they might have found their man—Ewan ‘The Elk’ Cartwright—who they invited to camp as a ‘walk-on’. The rest of the story is a relatively obscure piece of Bruins history.

Bruins fans of the last 50 years often ruminate over ‘what could have been’ if the likes of Bobby Orr or Cam Neely had not experienced career-shortening injuries. Former Bruins’ general manager and team president Harry Sinden adds two more names to that list—Steve Larmer and Ewan Cartwright. Larmer was a star right-wing for the Chicago Blackhawks in the 1980s who tallied 441 career goals and 1012 points over his NHL career, and Sinden came tantalizingly close to acquiring him in a trade at the prime of his career. Cartwright was a 6-foot, 200-pound scoring machine from the Western Canada Hockey League who, through fortuitous circumstances, became available on a try-out basis in 1976. “If either of those moves had come to fruition, we might have won another Cup or two. The Cartwright thing haunted me for years,” grumbled Sinden.

A product of Elkwater, Alberta, a hamlet southeast of Medicine Hat, Ewan Cartwright made a name for himself across the Alberta region as a dominant hockey player in the early 1970s. He was certainly as peculiar as he was productive. Cartwright was a box office draw, not just for his skills but for his pizazz. If you were not lucky enough to live within the same orbit of “The Elk” of Elkwater, you truly missed out.

In junior hockey, Cartwright was known to wear a matador’s cape during pregame skates. In games in which he scored, he was often seen post-game donning a headgear of prodigious ‘elk antlers’—a gift donated by an adoring fan during his youth days. ‘The Elk’ also carried a banjo with him on all road trips, often playing for teammates, media personnel, and fans alike. He had mastered the instrument by the age of 12. He fondly recalls taking summer banjo lessons from Sister Ethel of Our Lady of Virtue School for the Blind, marveling, “She had a mean clawhammer style. In fact, she let me play in the orphanage’s string band now and then. Boy, I dug that nun.”

Off the ice Ewan Cartwright loved to converse with anyone who would listen—whether it was his passion for philosophy (after his playing days, he earned a bachelor’s degree in Eastern philosophy) and human consciousness, his love of cooking, or his commentaries on social issues. In fact, Cartwright was a vocal proponent of the Vietnam War. Like thousands of other Canadians had elected to do, he wished to serve in a combat role in order to fight communist aggression in Vietnam. Fully committed, he attempted to sign up for service at the age of 19. However, due to his birth defect, Cartwright was turned away; he was born with a right leg two full inches shorter than the left, more than enough to label him a military 4-F. “While Americans were crossing the Canadian border to evade the draft, I would have gladly taken their place to fight the ‘commies’,” Cartwright recalled about the turbulent time period. “But what are you gonna do? Acceptance is light.”

One would think such a physical impairment might affect a player’s skating, but Ewan never let it stop him. “If you think my skating was rough, you should have seen me run,” joked Cartwright. “I loped like an injured deer.” Thus the longstanding nickname—’The Elk’. “Mom joked it was because I didn’t want to leave the womb. The left leg—the longer of the two—was entrenched, and they had to extricate me by pulling like you would a Stretch Armstrong!” exclaimed Cartwright. He suffered childhood slights as a teetering ambulatory child, but once introduced to ice skates, young Ewan began to quash his peers’ hurtful slurs.

Though his skating was irregularly choppy due to the skewed stance—often resulting in dizzyingly circuitous routes, followed by ambling shuffles as if to gain back his equilibrium—he appeared to have an uncanny sense of where the open ice was at all times. According to former Medicine Hat teammate Blinky Duggan, it was “like he had a built-in echo-location device that homed in on the opponent’s net.” His minor league linemate gushed, “One second he’s doing what seems to be aimless ‘figure-eights’ in the slot, the next second he’s lifting the puck into the top corner.” His minor league coaches marveled at his on-ice balance. No one seemed to be able to knock him off stride. The shorter right leg became a valuable push-off propeller of sorts. Cartwright likened it to his other right side extremity, his banjo-strumming hand. “While the left hand exerts the power—squeezing up and down the fretboard—it’s the strumming right hand that maintains my staccato rhythm, the magic. Same with my skating style. I literally skated the way I played the banjo. To some, it may not have been the sweetest music, but to me, it had a swing to it. To each his own.”

There is no evidence the Boston Bruins knew anything of Ewan Cartwright’s political leanings or banjo abilities, but there was no hiding the right-wing’s scoring prowess. Sinden recalled that “our scouts loved his potential.” For two straight seasons, Cartwright led the Medicine Hat Tigers in goal scoring, with 52 and 67 in 1974 and 1975. He still holds a professional hockey league record for scoring hat tricks in six straight games. The Medicine Hat star then chased the money and signed a one-year contract to play with the Chicago Cougars of the teetering World Hockey Association. Unfortunately, the team folded only two weeks later, and the contract was nullified. ‘The Elk’ loped home—”tail between legs,” as he puts it. Without a hockey team or source of income, Cartwright worked a variety of odd jobs, including car sales, philosophy research for a small community college, and even a short-lived stint as a kissing booth operator—a part-time opportunity which ‘The Elk’ admitted did not do much for his salary or his marriage. “You know, I was a handsome young man, but my wife didn’t like it, so she left. Hey, eventually, bubbles pop.”

Fortunes changed, however, in the summer of 1976. The Boston Bruins called and invited Cartwright to training camp as a walk-on project. Sinden felt that right-wingers Earl Anderson and Gordie Clark weren’t panning out for Boston in recent seasons, and a special invite to Cartwright, who was languishing at home in Elkwater playing in a recreational league, was worth a shot. Sinden shrewdly saw it as an opportunity to bolster the right side of his forward lineup or at least challenge the incumbents. Ewan was over the moon when he got the phone call and was determined to win the organization over and secure an NHL contract. “I arrived one week early and crashed with Bobby Schmautz. We drank a lot of beer and took even more slappers behind his apartment complex,” he remembers. “We set up beer cans along the concrete embankment for target practice. Schmautzy’s slappers often ended up sailing high over the wall, somewhere onto the expressway. More often than not, I hit my targets.”

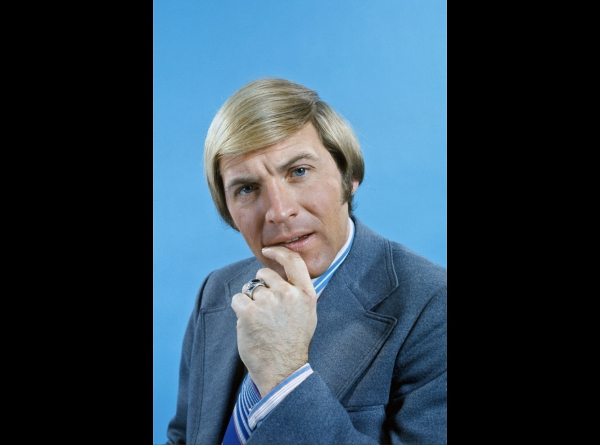

During training camp, the rugged winger was featured in the Boston Globe’s Parade Magazine (see attached photo from the photo shoot), showcased as a “can’t miss kid”, “eligible hockey hunk”—and perhaps most glowingly—as head coach ”Don Cherry’s secret weapon.” Also of note in the article were details of Cartwright’s philanthropy for the “Boston Women’s Fund” (“I was really volunteering just to meet broads”), a highly complimentary paragraph from Cherry about the walk-on being the best forward in camp after one week (“I scored on Cheevers on my first eight shots, and Cherry was teasing him mercilessly that he should take the rest of camp off and head back to the racetrack”), and a quote of his own to conclude the exposé where he appeared to prophesize the following: “Barring an injury, I don’t foresee any way I’m not on the Bruins’ roster come opening night.”

Man makes plans, and God laughs. Three days after the exposé—and two days before camp broke—in walked fate with malice and a sharp sense of humor. As a hobby during the prior year’s hockey hiatus, Cartwright had begun constructing hollow body banjos for friends and musicians. He was quite proud of his craftsmanship and cutting method. While showing Bruins trainer Frosty Forristall his technique on a table saw, his grip suddenly slipped, and destiny took a turn. “The blade made a choppy slice through my hand—as fast and deliberate as cutting through a slab of ham at the deli,” Cartwright reflected. “Knuckles everywhere!” ‘Elk’ meat has never spoiled so quickly.

Miraculously, the mishap caused no discernable pain. Whether it was his body’s shock response or Cartwright’s years of Chakra meditation training, he doesn’t recall any discomfort, only numbness. “I swear it was painless,” he shared. “Taz (Terry O’Reilly, the Bruins resident bruiser) had inflicted worse pain on me throughout training camp. It was nothing.”

Forristall tossed the hand remnants in a bucket of ice, wrapped Cartwright’s hand, and sped him to Mass General Hospital. There wasn’t anything the surgeons could do, however. He had damaged all four fingers of his right hand—the two middle fingers were sheared clean off, and the index finger and pinky suffered severe nerve damage. Just as fast as Ewan “The Elk” Cartwright had severed his fingers, the Bruins severed ties with the hockey player. He had not yet officially made the team, and he had no contract to show for his efforts.

“My hockey playing days were over,” Cartwright lamented. Instead of starting on a line with Gregg Sheppard, whom he had teamed up with to accumulate 15 points over the course of four exhibition games, the 24-year-old would be returning home to Alberta, his NHL dreams dashed. Almost as heartbreaking as the loss of a hockey career was the injury’s curtailment to his banjo playing. “It was my fret hand. If it were my strumming hand, I’d still be playing today,” he claims.

The hobby that ultimately led to his life-altering injury has since blossomed into a successful banjo manufacturing business—Cartwright Clawhammers, specializing in all wood, open-back banjos. It’s Canada’s fifth highest-selling banjo manufacturer. Since the injury, he’s much more careful while using the table saw. He’s also been aided by a prosthetic hand over the last few decades—”But sometimes I take it off and forget where I leave it. My grandson was surprised to find it in the gerbil cage the other day,” he chuckled. “What are you going to do? Life is funny.”

Ewan Cartwright played hockey just like he played banjo—with abandonment and pluck. As for his Bruins memories, he says he will never forget the summer and fall of ‘76. As for Bruins’ fans—if you have made it this far down the rabbit hole—Cartwright wishes you a happy ‘April Fools’ Day’.

*All content from this piece is purely fictional. Happy April Fools’ Day! The provided hockey photo of ‘The Elk’ is actually former NHL player Paul Weir.

Leave a Reply